Performance Post: Training Throwing Athletes Overhead Part 1

Performance Post: Training Throwing Athletes Overhead Part 1

There are a few topics of conversation that can turn any friendly discussion amongst strength and conditioning coaches into a passionate, heated debate: the

There are a few topics of conversation that can turn any friendly discussion amongst strength and conditioning coaches into a passionate, heated debate: the depth to which athletes should squat, whether or not Olympic lifts are necessary for training power, and the appropriateness of training throwing athletes overhead.

I'll be doing a two-part article on the last topic — training throwing athletes overhead. Good strength coaches fall on either side of the issue and have rationale for doing so. I am a staunch advocate for training throwing athletes overhead, and while I’m going to explain my rationale for my philosophy of training in next week's article, the important objective of this article is for coaches, parents, and players to gain a better understanding of the shoulder itself.

Training throwing athletes overhead, particularly with

Olympic weightlifting movements is a hotly debated subject

The anatomy of the shoulder is a give-and-take; it allows for a huge range of mobility but with that mobility comes instability. In contrast, the hip is an extremely stable joint with marked immobility compared to the shoulder. The mobility of the shoulder is good; it is what makes the overhand throw possible, but care must be taken when training the shoulder because of the unstable nature of the joint.

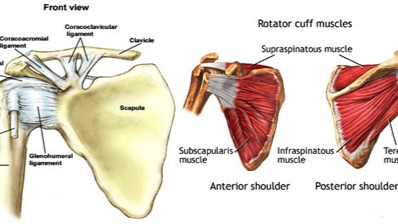

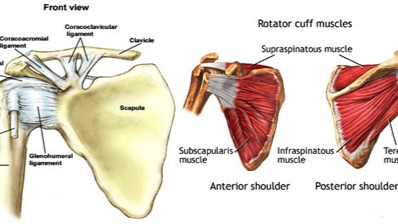

Short of a thesis-length discussion on the anatomy of the shoulder, suffice it to say that the stability the shoulder does have is made possible by muscles that overlay the intersection of bones —the rotator cuff— and ligaments that connect bone to bone. Contrary to popular belief, the rotator cuff is not a single muscle but rather a group of muscles and their tendons that attach the muscles to the bones in the shoulder. The four rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

The muscles, tendons, and ligaments of the shoulder

Hopefully with that brief and simplified explanation and picture you have some understanding of just how intricate the shoulder joint really is. Now on to training the shoulder. Conventional wisdom in training the shoulder is to increase its flexibility through static stretching and increase the strength of the rotator cuff muscles in isolation. Both of the aforementioned strategies are essentially useless and here’s why.

Static stretching is essentially holding a position of a muscle for at least 30 seconds, gradually lengthening it and increasing flexibility of the joint. Think of the classic arm across chest stretch or internal rotator cuff stretches for the shoulder. The problem with static stretching to increase the range of motion for a dynamic movement like throwing is two-fold.

This typical shoulder stretch does little to increase

throwing performance and improve shoulder health

First, we’ve already established that the shoulder is a complex joint with many muscles, tendons, and ligaments that work in conjunction with one another to make movement possible. Isolating a muscle in that complex system and stretching only it accomplishes very little because that stretched muscle never functions in isolation of the other muscles. Second, throwing is a dynamic movement, requiring sequential contractions of the muscles in and surrounding the joint. A dynamic movement like throwing requires dynamic — not static — flexibility. Dynamic flexibility involves moving the joint through an increasing range of motion. Movement is the key word there because dynamic flexibility requires movement, not static holding, and is controlled by the nervous system and is velocity specific.

All of the above basically sums to this: if you’re trying to increase the range of motion through a joint for sports performance, you must move the joint through that range of motion at a velocity comparable to the you’re trying to increase. Statically holding the muscle to lengthen it makes little logical sense and is not a physiologically sound practice if increased performance is your goal.

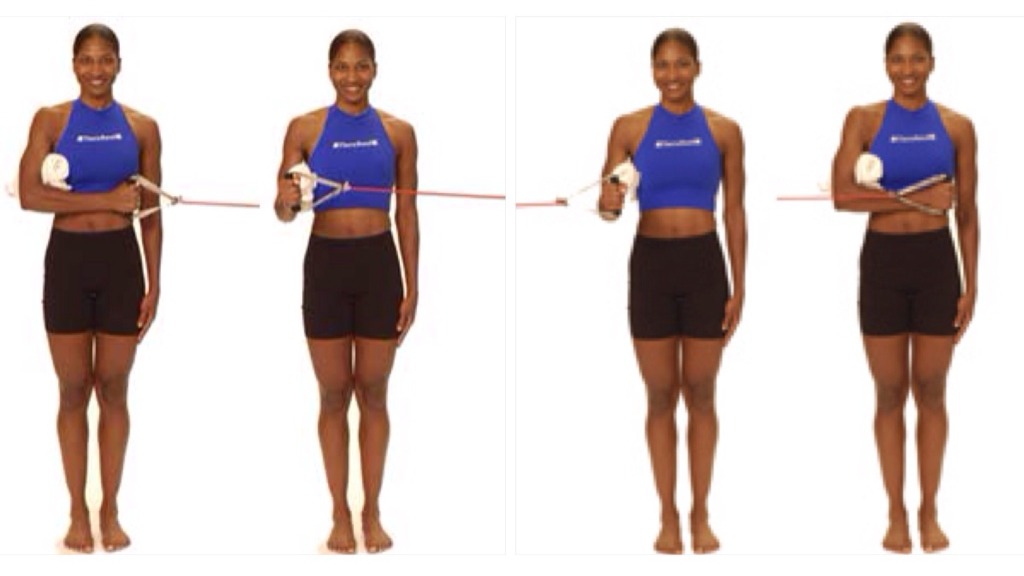

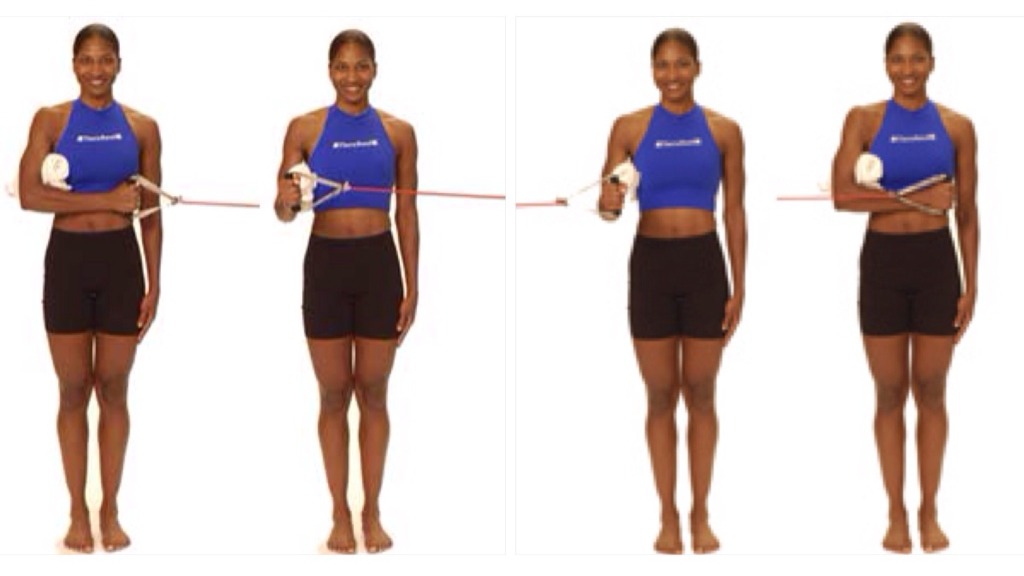

The other piece of conventional wisdom in training the shoulder is to increase the strength of the rotator cuff muscles in isolation. For this, picture the typical internal and external rotation exercises with bands. The same reasons why isolating muscles to stretch do little to increase the health and performance of the shoulder apply to strengthening the muscles of the shoulder in isolation as well. The shoulder is made up of multiple structures that all work in synergy to create movement; strengthening one muscle independently of the others does nothing! In addition, the shoulder muscles aren’t the only muscles used to throw. Other muscles involved in throwing are the pectoralis major (chest) and latissimus dorsi (back) and should be trained in conjunction with the muscles of the shoulder when training to increase throwing performance.

Typical rotator cuff strengthening exercises are better

suited for therapy than performance

Hopefully you're beginning to understand that better ways exist to train the shoulder than the conventional methods that are widespread in strength and conditioning. I spent four years at two prominent Division I universities and saw these less than adequate methods for training the shoulder used by coaches on a regular basis, so let me be clear — nothing I mentioned in this article will harm the shoulder, and both static stretching and isolation strength work have their place in a training program. But there are better, more comprehensive ways to train the shoulder for performance.

So how should the shoulder be trained? I’ll be covering that in part 2 of Going Overhead: Training Throwing Athletes next week!

I'll be doing a two-part article on the last topic — training throwing athletes overhead. Good strength coaches fall on either side of the issue and have rationale for doing so. I am a staunch advocate for training throwing athletes overhead, and while I’m going to explain my rationale for my philosophy of training in next week's article, the important objective of this article is for coaches, parents, and players to gain a better understanding of the shoulder itself.

Training throwing athletes overhead, particularly with

Olympic weightlifting movements is a hotly debated subject

The anatomy of the shoulder is a give-and-take; it allows for a huge range of mobility but with that mobility comes instability. In contrast, the hip is an extremely stable joint with marked immobility compared to the shoulder. The mobility of the shoulder is good; it is what makes the overhand throw possible, but care must be taken when training the shoulder because of the unstable nature of the joint.

Short of a thesis-length discussion on the anatomy of the shoulder, suffice it to say that the stability the shoulder does have is made possible by muscles that overlay the intersection of bones —the rotator cuff— and ligaments that connect bone to bone. Contrary to popular belief, the rotator cuff is not a single muscle but rather a group of muscles and their tendons that attach the muscles to the bones in the shoulder. The four rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

The muscles, tendons, and ligaments of the shoulder

Hopefully with that brief and simplified explanation and picture you have some understanding of just how intricate the shoulder joint really is. Now on to training the shoulder. Conventional wisdom in training the shoulder is to increase its flexibility through static stretching and increase the strength of the rotator cuff muscles in isolation. Both of the aforementioned strategies are essentially useless and here’s why.

Static stretching is essentially holding a position of a muscle for at least 30 seconds, gradually lengthening it and increasing flexibility of the joint. Think of the classic arm across chest stretch or internal rotator cuff stretches for the shoulder. The problem with static stretching to increase the range of motion for a dynamic movement like throwing is two-fold.

This typical shoulder stretch does little to increase

throwing performance and improve shoulder health

First, we’ve already established that the shoulder is a complex joint with many muscles, tendons, and ligaments that work in conjunction with one another to make movement possible. Isolating a muscle in that complex system and stretching only it accomplishes very little because that stretched muscle never functions in isolation of the other muscles. Second, throwing is a dynamic movement, requiring sequential contractions of the muscles in and surrounding the joint. A dynamic movement like throwing requires dynamic — not static — flexibility. Dynamic flexibility involves moving the joint through an increasing range of motion. Movement is the key word there because dynamic flexibility requires movement, not static holding, and is controlled by the nervous system and is velocity specific.

All of the above basically sums to this: if you’re trying to increase the range of motion through a joint for sports performance, you must move the joint through that range of motion at a velocity comparable to the you’re trying to increase. Statically holding the muscle to lengthen it makes little logical sense and is not a physiologically sound practice if increased performance is your goal.

The other piece of conventional wisdom in training the shoulder is to increase the strength of the rotator cuff muscles in isolation. For this, picture the typical internal and external rotation exercises with bands. The same reasons why isolating muscles to stretch do little to increase the health and performance of the shoulder apply to strengthening the muscles of the shoulder in isolation as well. The shoulder is made up of multiple structures that all work in synergy to create movement; strengthening one muscle independently of the others does nothing! In addition, the shoulder muscles aren’t the only muscles used to throw. Other muscles involved in throwing are the pectoralis major (chest) and latissimus dorsi (back) and should be trained in conjunction with the muscles of the shoulder when training to increase throwing performance.

Typical rotator cuff strengthening exercises are better

suited for therapy than performance

Hopefully you're beginning to understand that better ways exist to train the shoulder than the conventional methods that are widespread in strength and conditioning. I spent four years at two prominent Division I universities and saw these less than adequate methods for training the shoulder used by coaches on a regular basis, so let me be clear — nothing I mentioned in this article will harm the shoulder, and both static stretching and isolation strength work have their place in a training program. But there are better, more comprehensive ways to train the shoulder for performance.

So how should the shoulder be trained? I’ll be covering that in part 2 of Going Overhead: Training Throwing Athletes next week!